If you’re an outdoorsperson of any kind, hearing “El Niño” or “La Niña” probably elicits a feeling within you, for better or worse. In a bizarre popularization of an otherwise technical meteorological term, it seems that anyone with a vested interest in winter weather has an opinion on El Niño and La Niña, but what are these two phenomena in the first place, and what do they mean for this winter in Central Oregon?

On November 9, 2017, the National Weather Service predicted a 65-75% chance of a “weak La Niña” for winter 2017-2018. This prediction follows a relatively short 2016-2017 La Niña and a 2015-2016 El Niño that was one of the strongest in history.

To understand either El Niño or La Niña—Spanish for “the little boy” and “the little girl,” respectively—you first have to take a dive into the oceanic system known as El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO.

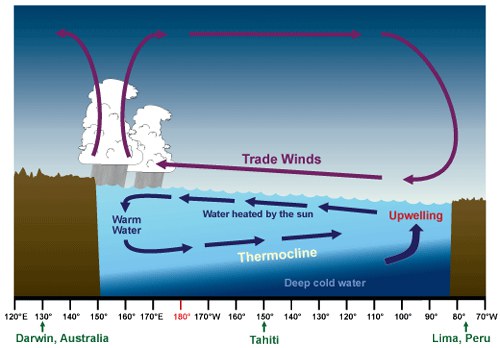

ENSO is constant, and you can think of it as warm water sloshing back and forth—or oscillating—very slowly across the Pacific Ocean. El Niño and La Niña are just specific ENSO scenarios that can determine which direction the water sloshes in a given year.

- In a normal year (image below), easterly trade winds (winds that blow from east to west) carry warm air from the Americas toward Asia. This piles up warm water on the west side of the Pacific, which allows cold, deep water to rise to the ocean’s surface along the coasts of South, Central, and North America. This is known as upwelling, and the cold water brings with it important nutrients that contribute to coastal ecosystem and fisheries health, particularly in South America.

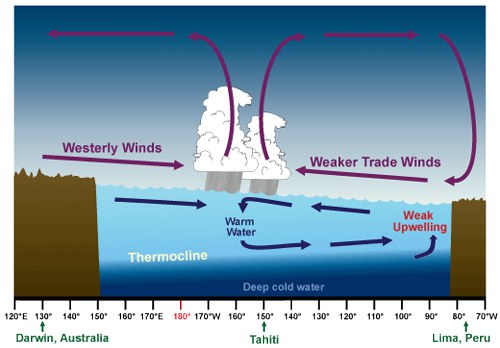

- In an El Niño year (think the winter before last), the normal ENSO pattern reverses as pressure changes in the western Pacific and surface sea temperatures increase at least 0.5ºC above a normal year (see image below). These changes weaken trade winds and allow more warm water to stay near the Americas. The warmer than average temperatures devastate fish populations in Peru and Ecuador, create big surf all along the coast, and lead to increased precipitation (and incredible skiing) in California’s Sierra Nevada range.

As for Oregon, El Niño usually brings warmer than average temperatures across the state, and particularly in the Cascades. While this isn’t a death sentence for ski season, it’s usually an indicator of less-than-desirable snowfall.

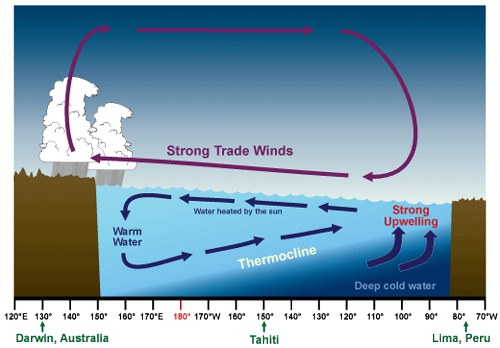

- La Niña events, by contrast, basically enhance all of the components of ENSO. Easterly trade winds become even stronger, leading to increased upwelling along the Americas and an average sea surface temperature drop of at least 0.5ºC. While it’s too early to know exactly how La Niña will impact Oregon this year, La Niña generally does increase the chances of heavy storms and precipitation, particularly in the Cascades.

Remember last winter in Bend? Yeah, that was La Niña.

So, whether you’re hoping for snowpack to support spring stream flows and fish health, or you just want to make sure that the Bachelor season pass you bought in September will ultimately pay off, La Niña could bring much to be thankful for this winter.

Learn More:

- The basics of El Niño and La Niña.

- Effects of El Niño Southern Oscillation in the Pacific Ocean.

- Forecasts for winter 2017-2018 in Oregon.