Thanks for choosing to learn more about the Santiam Wagon Road! Wagon Road materials are provided in the following formats:

- Folleto: Leer en español. Carteles interpretativas: Leer en español.

- Brochure: Download as a PDF in English. Interpretive signs: Download as a PDF in English.

- Listen with an audio reader. (Download PDF first).

In the 1860s, a new road was built over the central Cascades connecting the valley to desert.

This newly built road, the Santiam Wagon Road, helped people travel more easily from the Willamette Valley across the rugged Cascades, to the forests, meadows, and deserts of Central Oregon.

Where did the road lead in the high desert? What was it like to travel back then? Learn more below.

Connecting Valley and Range

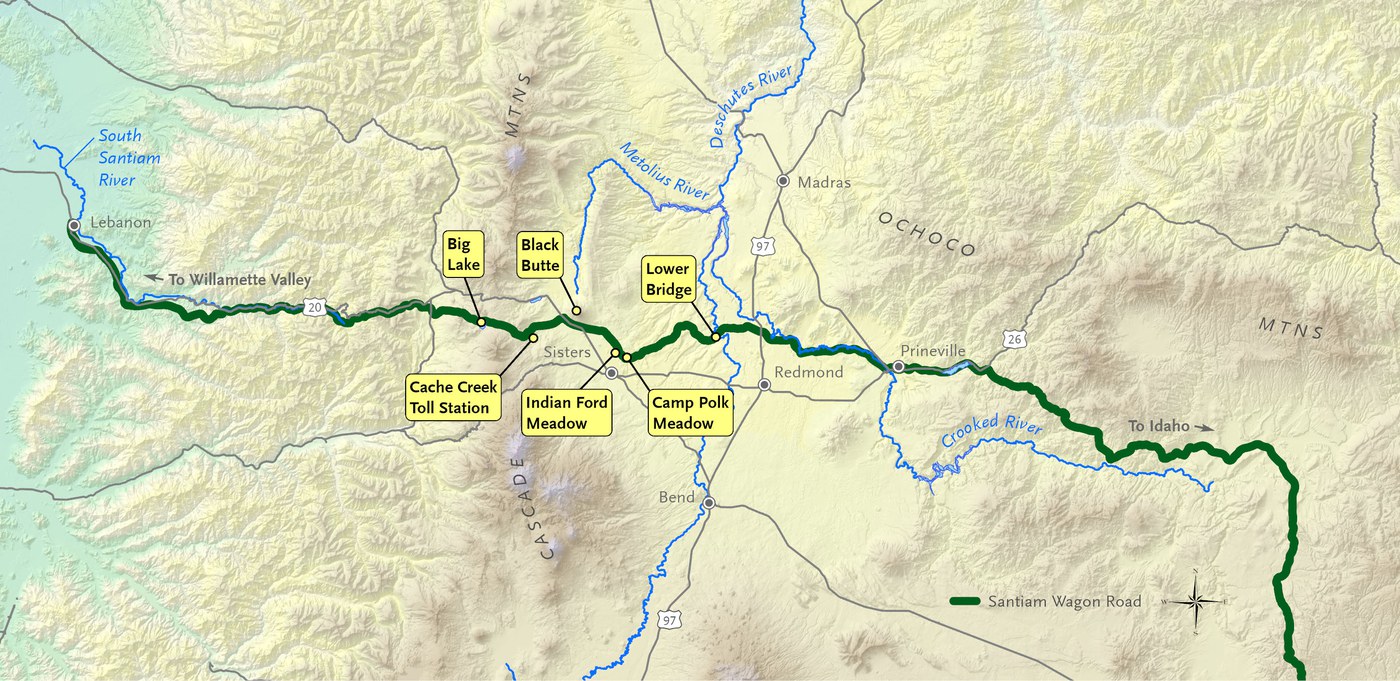

The Santiam Wagon Road was built in the 1860s to connect the Willamette Valley to the open rangelands of eastern Oregon and the gold camps of eastern Oregon and Idaho. Like many wagon roads, it followed well-known trails and travel corridors used by Native Americans. It was nearly 400 miles long and served as a livestock trail and freight route over the middle section of the Cascades.

Lebanon, Oregon was a supply and restocking point for travelers. The first few miles of the Wagon Road were established here in 1861. The Central Oregon Wagon Road took travelers around Black Butte, followed Indian Ford Creek, past Camp Polk Meadow, and east through the desert to cross the Deschutes River at Lower Bridge. Canyon City and John Day, Oregon were destination points for Wagon Road merchants looking to sell their wares to gold miners. Burns, Oregon was the end point for the “official” Wagon Road. Beyond this point the route to Idaho was only marked by stakes in the sand.

Eastward Travel

Why were settlers from the Willamette Valley heading to the high desert to graze their cattle? By the 1860s, the Willamette Valley was getting crowded. Population growth combined with private land ownership limited open range for grazing. The Santiam Wagon Road allowed ranchers to access open range in Central Oregon, and it helped merchants and freighters reach the growing gold mining populations in eastern Oregon and Idaho.

Ranchers traveled the Santiam Wagon Road to graze their livestock on the less crowded range of Central Oregon. The photo above show how different the landscape looked at the time of the Santiam Wagon Road. Compared to today, there were fewer juniper trees, more scattered sagebrush, and taller native bunchgrasses. Unfortunately, the native bunchgrasses weren’t adapted to intense grazing by livestock, but rather the occasional browsing by deer and elk. The hope for endless food for livestock quickly disappeared.

Cattlemen and Gold Miners

Willamette Valley merchants were also lured east by the gold rush in John Day and Canyon City where gold country populations topped 10,000. The photo at left shows City Brewery in thriving Canyon City, where gold was first discovered in 1862. Canyon City’s population in 2020 was 660.

The Land Grab

The people who built the Wagon Road received official government designation allowing them to build and claim large tracts of public land. In the end, the road company took possession of 861,512 acres of public land.

Westward Travel

Westward traffic on the Santiam Wagon Road consisted of wool wagons in long “trains” often half a mile long, traveling from Shaniko (near Madras) with wool for mills in the Willamette Valley towns of Waterloo, Brownsville, and Jefferson. Ranchers in the eastern part of Oregon also traveled westward for as long as a week to get a load of fruit and vegetables to take home for the winter.

The late 19th century saw an expansion in sheep raising, as the federal government forcibly resettled Native Americans and offered western lands to Euro-Americans. Central Oregon was prime sheep raising territory, with herders grazing sheep in the Cascades in summer and in lower elevations during winter. Sheep also willingly ate the “weeds” left behind from cattle grazing.

Big Business

Sheep were big business in Central Oregon at the time of the Santiam Wagon Road. By 1900, 20,000 square miles of Central Oregon were devoted to wool, wheat, cattle and sheep production. Wool growers had to travel the Wagon Road to get their wool to the Willamette Valley mill towns.

Wool Capital of the World

Over time, wool business moved away from the Wagon Road to Shaniko, where the Columbia Southern Railway ended. In 1900, Shaniko was the “Wool Capital of the World”, serving as the gateway to wool markets beyond Central Oregon.

Reconstructing Routes

Today, modern LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) technology can be combined with historic maps and documents to reconstruct the path of the Wagon Road. LIDAR uses lasers to accurately map landform contours beneath any surface vegetation.

Finally, physical evidence, such as old tree blazes, wheel ruts, or piles of rocks (cleared to make a path for the wagons), can also help with reconstruction. For example, at Whychus Canyon Preserve, there is evidence of ruts left by wagons and piles of rock thrown off to the side of the road or used to fill in depressions.

The End of an Era

The The Santiam Wagon Road served as a livestock trail and the only freight route over the central Cascades for most of the 74 years (1865-1939) it was in use. It spanned a distance of almost 400 miles on today’s roads and provided passage for around 5,000 wagons during the first 15 years of its existence.

Over time, the era of wagons and wagon roads made way for the new modern world of cars. The Oregon Trunk Railway line, completed in 1911, ran from the Columbia River up the canyon of the Deschutes River to Bend. The railway and the arrival of automobiles spelled the end of the Wagon Road. The first car, “Old Scout,” came to Central Oregon in 1905 and “Old Steady” (pictured at left) arrived in Prineville shortly thereafter. “Old Steady” suffered some damage during the early years, asone untrained user smoked a cigarette while fueling up (look closely!).

Wagons Make Way for Cars

By 1900, the Columbia Southern Railroad connected to Shaniko, diverting freight traffic, especially the wool wagons, away from the Wagon Road. By 1911, the Oregon Trunk Railroad reached Bend, further rerouting traffic. The road over McKenzie Pass opened in the 1920s and the Santiam Pass road opened in 1939, bringing automobiles, modern highways, and the end of an era.

Bibliography

See a list of sources the Land Trust and our volunteers used to create interpretive materials on the Santiam Wagon Road.

Thank you!

A thousand thanks to Carol Wall for her time and energy to research the Santiam Wagon Road and its connection to Deschutes Land Trust Preserves. Carol, you are the best!

Many thanks to Steve Lent at the Bowman Museum for his time reviewing these materials and for donating historical photos. Thanks as well to the Oregon Historical Society for help with historical photos and to the Bureau of Land Management for support of this project.

Finally, this project would not have been possible without the initial support of the Oregon Community Foundation's Oregon Historic Trails Fund. Thank you!